Piotr Kamler and the Machine City by Lauren Flinner

Piotr Kamler’s Chronopolis, made in 1983, is the kind of film that evades description, with its loose narrative structure and ambigious thematic message. Nonetheless, it is a remarkable and thought provoking work. As such, I thought it deserved a close and careful analysis. After looking at Kamler’s education and influences, with this background in mind, I will argue that Chronopolis paints a picture of a machine consciousness that is uncaring, tired of immortality, and craving death.

The topic of the machine is frequently explored in Modernist works and works of Science Fiction. What is unique about Kamler's film, however, is that this is only one interpretation and there is no clear moral. The viewer is asked to consider the physical qualities of what takes place within the frame and must construct meaning from this. Therefore, in this paper I will look at the ways that set and character design, performance, use of color and other symbols and motifs support a reading of Chronopolis as representative of a particularly weary conscious machine.

Proof of Chronopolis' enigmatic narrative can be found by perusing existing attempts at a plot summary. Here is my attempt: a group of explorers climb past a city in the sky. Within this city, stoic immortals pass the time by absentmindedly constructing abstract shapes. One of the explorers falls into the outskirts of the city. Upon observing this, the immortals construct a white sphere which they send to the fallen explorer. The explorer follows the sphere into the city where they meet the immortals. They are both placed in a kind of machine room, and seemingly, their presence causes the city to decay at the film's end.

While one can describe what takes place on screen easily enough, articulating what Chronopolis is about is a greater challenge. I believe this openness is one of the film's greatest strengths. This analysis focuses on one particular reading of the film's meaning: that the city of Chronopolis may be seen as a machine, and as such, it paints a portrait of what a machine consciousness might look like. While the crux of my argument involves visual clues from within the film itself, I have also considered the historical context within which Kamler was working.

Education and Involvement with Institutions

Piotr Kamler was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1936. He discovered animation while studying at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art. Prompted by the frustration he felt working with graphic arts, he decided to switch to time based art. He claims, “Everything was static, majestic. I had enough and decided to introduce movement. Dynamics, similar to musical elements, is for me the most important.”1 He moved to Paris in 1959, where he continued studying at the École des Beaux-Arts. The school emphasized classical art antiquities, which likely had an influence on the imagery in Chronopolis. In Paris, Kamler began working with the ORTF (Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française). The ORTF was the government agency responsible for France’s public radio and television from 1964 until 1974, at which point it was taken over by the INA (Institut National de l’Audiovisuel). The ORTF research department, led by concrete musician Pierre Schaeffer and subdivided into the Groupe de Recherche Musicale and the Groupe de Recherche Image, acted as a hub for multidisciplinary collaboration between artists, technicians and researchers. 2 During his involvement in the ORTF research department Kamler produced a number of experimental short films in collaboration with concrete music artists.3

Influence of Concrete Music

Concrete music is commonly seen as invented by Pierre Schaeffer. Its operating principle is that recorded sounds, either musical or natural, are in some way processed, for example by distortion or using filters. It is a highly experimental endeavor. In 1968, Humphrey Searle criticized the genre stating, “Musique concrete has been most successful in the evocation of dramatic atmosphere in background and incidental music; it has not yet been able to produce works which are musically self-sufficient.”4 While this may read as a negative assessment to a sonic artist, one can see how alternatively, an animator may have been inspired by a dramatic atmosphere of sound. Kamler must have been in some way energized by the musical genre, because he had Luc Ferrari, a concrete musician, compose the music for Chronopolis.

Influence of Paris: Surrealism And Modernism

Historically, French animators tended to work outside of major studios and typically produced more experimental work, disregarding the conventions of live action cinema.5 Richard Neupert notes that in France, “The explosion of truly avant-garde cinema during the 1920s began exploring the techniques but also the functions of animation in a surprising number of extreme experiments far beyond anything practiced in other national cinemas.”5 This experimentation was done mainly by independent animators: painters, designers, writers and poets who turned to animation individually and in small groups. The two major French film studios, Pathé and Gaumont were not producing animation, though they were distributing American cartoons.6 This auteur-centered and multi-disciplinary environment was also home to the Surrealist movement, although early Surrealist cinema, done by artists like Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, and René Clair, mainly took the form of live action. May Ray is the exception, producing Le Retour a la Raison in 1923 using animated pictograms.

It can be tricky to pin down a common aesthetic, but Surrealism’s main philosophical concern was the unconscious and irrational mind. Michael Gould notes, “A surreal film...takes one out of one’s conscious mind into the subconscious...If the vision revealed is too much for the rational mind to absorb...yet cannot be rejected, then it leaves the consciousness and comes to exist on a sublime level as pure surrealism.”7 Kamler aligns his own work with surrealism8. His vague synopsis for Chronopolis: an immense city in space whose inhabitants build time, does little to provide a logical anchor for the events that transpire in the film, leaving viewers to grapple with their impulse to create a cohesive narrative.

(Fig. 1) Le Corbusier's “Plan Voisin” has similarities to the design of Kamler's city in Chronopolis

Surrealism was one of the major movements of the Modernist period, which began in the 19th century and remained influential through the 1970s. At its start, the world was being transformed by technological advancements and Modernist artists associated the changes with a utopian dream of the future. At the same time, they spoke to a sense of anxiety at the rapidly changing environment. According to Robert Baldwin, Surrealism, “Had a conflicted fascination with the modern machine, at once reveling in mechanical forms as the paradigmatic visual sign of a uniquely modern, abstract art and playfully subverting the utilitarian, rational, impersonal values of the twentieth century "machine age.”9 Although Kamler was making Chronolopis in the early 80's, the start of the postmodernist era, he was influenced by surrealism enough to adopt it as a label for his own work. As such, it is not a stretch to read the repetitive and impersonal gestures of Chronopolis' immortals as a kind of surrealist machine.

The Genre of Science Fiction

Setting aside Kamler’s classification of his work, contemporary critics and fans frequently describe Chronopolis as a work of science fiction. The genre as a whole has historically been linked to Modernism, although critic Adam Roberts suggests that science fiction may represent either “Low Modernism” or “High Modernism”. The former is characterized by “hostility to technological change” while the latter embodied an uncritical sense of exhilaration.10 The 1920s and 1930s were known as the “pulp age” of science fiction, defined by space opera and melodramatic adventure in Sci-Fi literature. The general quality of the genre reflected “High Modernism.” Directly following the “pulp age” is the “golden age” of science fiction. Sci-Fi cinema of the “golden age” was primarily live action and focused on stories of monsters and alien invasions. Then the 50s and 60s brought about the “new wave” science fiction movement, which was characterized by more experimentation. During this era in France, science fiction tended to reflect a “Low Modernist” approach, criticizing trends in society. It was during this time that Piotr Kamler started working and whatever science fiction qualities his films possess, he was surely exposed to the narrative of the “new wave” movement.

Chronopolis: City As Machine

The notion of frustration at the passing of time is key to understanding the struggle of Kamler's city-machine. The constant symbolic presence of time suggests the machine mind is preoccupied with its relationship to time. Like the title would suggest, “time” is everywhere in Chronopolis. The film opens on an off white screen. The color is reminiscent of old paper and immediately denotes age. On the off white background we see a spotlight “swing” from the left side of the frame to the right side. The shot is extremely fast, lasting only one second, but this illuminated pendulum swing will be a recurring motif throughout the remainder of the film, including its last shot. As such, it acts as the film’s bookends, emphasizing the thematic importance of the passing of time. The quickness of the pendulum motif stands in contrast to many of the other sequences in Chronopolis, which play with comparatively long duration, putting the viewer in the position of wondering, “where is this going?”

(Fig. 2) The explorers

The remainder of the opening sequence of Chronopolis is a concentrated introduction to much of the film's content. Kamler places a strictly visual primer before the film’s opening textual summary, which encourages a poetic analysis of the physical qualities of the shots before a narrative or logic based valuation of the film. The opening pendulum fades into a swirling mass of clouds out of which emerges a mountain climber, one of many identical climbers hard at work scaling a vertical wall (Fig.2). This introduces the character of the explorer, and also points to the notion of the individual as part of an extended network, which stands in contrast to the immortal's “network as individual” consciousness. The explorer's ascent is intercut and overlaid with a series of quick shots. First, we see an upside down shot of what will later become clear is the city of Chronopolis (Fig. 3). This is the only time it is shown to be upside down. This visual trick acts to distance the city by implying that it is not in the same plane (physical or perhaps even dimensional) as the explorers. It also signals to the viewer that we are entering an alternate dimension where the traditions of narrative and logic may not apply. The subsequent cut-away shots include: chaotic and blurry overlaid geometric patterns, a pan of three sculptural and stoic humanoid figures, the “immortals” (Fig. 4), and a close up of a surface covered in a simple geometric design (Fig. 5). These shots suggest a linkage between the immortals and the geometry of the city, another key theme of the film. This series of shots happens quickly, but it acts as a near complete visual introduction to the characters and themes of the film to come.

(Fig. 3) The upside down city, (Fig. 4) The Immortals, (Fig. 5) Surface with geometric pattern

Throughout the film, Kamler plays with the correlation between the archaic and the technologic. When the film’s title appears it seems to be carved into a stone surface, which slowly erodes away. This stone quality features throughout the film, giving the immortals and their city an archaic and unmoving character. It implies permanence in the way of ancient ruins. Still, there is a kind of technologic energy to the stone structures. This is apparent in the first extended sequence of the film, wherein a seemingly endless series of interconnected square panels buzz with energy. Although they initially have no context, there is something unmistakably robotic about their design, further emphasized by the clinking quality of Ferrari's soundtrack.

The design of the city as a whole implies elaborate circuitry, which Kamler uses to explore notions of consciousness. There are interconnected tubes, assembly lines, spinning gears, flashing lights. All of these images can be said to have some relation to technology or machine processes. Kamler pairs these motifs with imagery associated with consciousness. After spending some time with the buzzing square panels, Kamler's dives into one with the camera, emerging out onto an environment reminiscent of outer space, wherein an endless series of doors within doors open onto each other. One may infer a comparison to the doors of perception, or more broadly, a generalized concern with expanded or alternative consciousnesses. At the very least, this moment places the city's mechanics within a cosmic context.

Analyzing the role the immortals play within the film further supports a reading of the city as a conscious machine. In the midst of the city's vast network sit the immortals, sending each other messages through their handheld gadgets and conjuring images on circular screens. It is easy to read the immortals as there to organize the different parts of the larger machine that is the city as a whole. The most direct visual proof that they are tied to the larger landscape comes at the end, when the immortals and the city decay in tandem. Before this culminating moment however, we see one immortal apparently hard at work sculpting various shapes. What is interesting about this moment is that it concentrates on an individual immortal in an isolated space. He does not seem to be communicating with anyone else. Kamler focuses on the immortal's repetitive gestures as he shapes meticulous abstract sculptures, which he then quickly and carelessly destroys. There is seemingly no purpose to these movements. So, perhaps Kamler is showing us the purposelessness of the machine consciousness when isolated from performing its designated tasks.

The overall color palate is of muted sepias: browns, tans, and grays. However, there are moments where a bright red stands out: the mechanical “heart” that is added to the ball, the rash like mark that appears on the ball's surface after it has been struck by a mechanical device during what looks like an endurance test, the flashes of red that appear when the explorer becomes obsessed with the ball, and the red tone of the ball itself in the final moments of the film. The movements of the ball are very simple: a squash and stretch bouncing that moves it forward. Yet, it conveys a sense of personality and consciousness as it moves through its environment, at one point seeming to hesitate at a ledge, later seeming to dance with the explorer. The color red is used to highlight its sentient qualities: the heart bringing it to life, the rash showing that it feels pain, the flashing of red indicating the connection between it and the explorer, with its ultimate transformation from white to red following the decay of the immortals being a final indication of its unique agency.

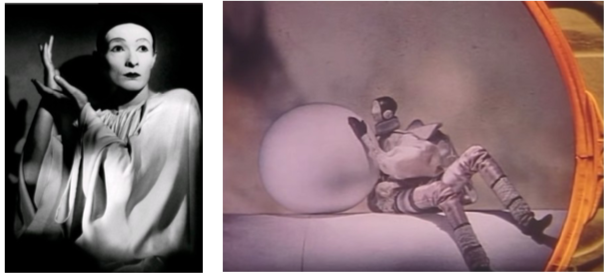

(Fig. 6) The similarities between the explorer's costume and for example, Jean-Gaspard Deburau

The explorer is costumed appropriately for a science fiction action adventure. In his puffy white jumpsuit, he almost looks like an astronaut. Moreover, his small head with his white face and dark black hair vaguely suggest a mime. This mime-like quality matches the dancerly, naive optimism of his movements throughout the film. On the other hand, the statue-like immortals barely move. Their robes connote mystic importance and their circular headdresses reference their unending nature. Their expressions do not change and mostly convey boredom, disinterest, or at most absentminded determination. There is a clear contrast between the stoicism of the immortals and the playful curiosity of the explorer and the ball. It may be that Kamler is linking immortality with not only boredom but with something inhuman. Supposing a reading of the immortals as part of a great machine city, perhaps they represent its sentience. They are the awareness of the machine, bored and craving death.

What Does It Mean?

In my analysis of Chronopolis so far I have mainly looked at Kamler's construction of images, scrutinizing the symbolic importance of elements within the frame, and at most considering what isolated moments of performance can tell. I have concluded that an understanding of the city as machine, with the immortals as the machine consciousness, can be derived from the information within the frame. For the remainder of my analysis I would like to attempt to specify a potential narrative structure, and consider its significance within the the framework of a conscious machine-city. While elements within the frame will still provide useful in shaping an understanding of Kamler's narrative, my analysis will concern the implications of said narrative for the meaning of the film at large.

A key narrative element is the fact that the immortals seem to purposefully lure the explorer to them. With this gesture, Kamler shows that the immortals have at least an understanding of human interactions, and the importance of individuality and relationships and intimacy even if they may be unable to experience any of these themselves. The explorer is shown to be part of a group, but he is still a separate entity. The immortals create the ball in order to communicate with the explorer, but because their consciousness would be alien and inaccessible to the mortal explorer, they imbue the ball with an individual personality and consciousness. This can be read as an attempt to relate to the explorer by appealing to his sense of curiosity and camaraderie.

(Fig. 7) Immortals creating the bird, (Fig. 8) The bird marks a separation

There are two fundamental moments that illustrate this balance of intimacy and distance. The first is when we see the indifferent and stone faced immortals send what appears to be a bird to separate the explorer from his companions, sending him hurtling toward their ancient city (Fig. 7&8). The explorer's fall is chaotic, sending him tumbling and hurtling both downwards and upwards. Ferrari's music sounds like a choir of voices extending a single sour note, which adds to the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty. Importantly, before the explorer reaches his final landing point, Kamler shows him floating above the immortals absented minded sculptures. This pairing contextualizes their relationship to the explorer. Like their sculptures which they so readily destroy, they show no concern at dramatically altering this individual's fate. Because of this narrative relationship the immortals are made to seem more inhuman.

(Fig. 9) The explorer caresses the ball, (Fig. 10) Their intimacy intensifies

In contrast, the relationship between the explorer and the ball shows deep intimacy and connection. This intimacy between individuals becomes important when considering their role in the ultimate destruction of the city. After stumbling onto the ball, the explorer gently and sweetly caresses it as if he wants to care for it(Fig. 9). Kamer shows the intensity of their connection when they begin to spin and a dark red color flashes over them.(Fig. 10) They emerge from this profound chaos into a dance, wherein they are moving in sync with each other. This synchronization suggest that the duo share a connective network, comparable but dissimilar to that of the city. What marks it as different is the intimacy, rather than indifference, that it sprung from.

(Fig. 11) The pair is plugged in, (Fig. 12) An immortal decaying

What did they intend by leading the affectionate pair into their city and instigating their own destruction? One can argue that they meant to study the pair, to learn how to be like them. I believe that, considering their previously established extreme boredom and preoccupation with the monotony of eternity, as well as their indifference to the well being of the explorer, that they were intentionally attempting to bring about their demise. They did so by introducing ephemeral network of individual intimacy into their unending and uncaring machine network, which it could not understand or integrate(Fig. 11). This caused a short circuit, resulting in their end, which was very much looked after and welcomed(Fig. 12).

Conclusion: In Contrast

Kamler’s films have won numerous awards, including the Grand Prix at Annecy for Le Pas (1975). However, despite their critical success, they remain relatively unknown to a larger audience (Chronopolis has failed to achieve the cult status that other Sci-Fi or Sci-Fi adjacent animations have developed). To that extent, it may be interesting to reflect on the work of René Laloux, a filmmaker working in science fiction animation at the same time as Kamler whose work has managed to secure a cult status.

(Fig. 13) Fantastic Planet

Laloux's Fantastic Planet (1973), which won the Special July Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, is a work of allegorical science fiction. Its plot, which unlike Chronopolis has a clear narrative progression, centers on an alternate universe where humans are kept as pets of an alien race called the Draags. Richard Neupert notes, “Much of Laloux’s work revolves around comical nightmare scenarios that implicate humanity as the ultimate cause for throwing the world out of balance. Even when the action is whimsical, Laloux’s work comes with a warning.”11

Though human characters are the victims in Fantastic Planet, there is a clear warning against prejudice and abuse. There is also a happy ending that exhorts rationality and peace. This is perhaps the largest difference between René Laloux’s filmography and the films of Piotr Kamler. Even though the scenes in Chronopolis seem to suggest some kind of undisclosed narrative, the film’s ambiguous moral lesson is perhaps a greater challenge for audiences familiar with the value judgments and warnings that tend to come with science fiction. Chronopolis is neither a “Low Modernist” space opera, nor a “High Modernist” social critique. In that way, the network Kamler establishes between the viewer and the film is more like the intimate sharing between the explorer and the ball than the way information is conveyed within his uncaring and certain city. Much more could, and should be written about this, as well as Kamler's other films.

Works Cited

1. "PIOTR KAMLER." Mubi. Accessed October 1, 2016. https://mubi.com/cast/piotr-kamler.

2. Évelyne Gayou, “The GRM: Landmarks on a Historic Route” Organised Sound: Vol. 12, No. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 203-211.

3. Giannalberto Bendazzi, Animation: A World History: Volume II: The Birth of a Style - The Three Markets (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2016), 177-78

4. Humphrey Searle, Twentieth Century Music. Edited by Rollo H. Myers (New York: The Orion Press, 1968)

5. Richard Neupert, French Animation History (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2011)

6. Neupert

7. Michael Gould, Surrealism and the Cinema (London, UK: The Tantivy Press, 1976)

8. Bendazzi

9. Baldwin, Robert. "SURREALISM (1924-1945)." Social History of Art. Accessed October 1, 2016. http://socialhistoryofart.com/

10. J.P. Telotte, “Animation, Modernism, and the Science Fiction Imagination” Science Fiction Studies Vol. 42, No. 3 (November 2015), pp. 417-432

11. Neupert